And so it happened and, eerily, went roughly to plan. Instead of rehearsals we had planning. From the angles of loose rice at rest we calculated volumes and floor prints. We established how many millions would sit per metre on our wide rolls of paper; how much paper we would need of what size; how many forklift days wed need and how many performers for how long; how many bags in which piles and how many would remain unopened at the end?

With a scale plan of the Waggenhalle and cut-outs for the rice features, we sketched in flimsy paper what would become hours of back-break. We had only ever seen the hall piled high as a Flohmarkt; now, empty, it took our breath away. Too big to compete with, too full of character to ignore, we had to collaborate with the building. The monumental steel topped table we found there became the centrepiece, the crane its backdrop and inspection steps a twist. A metallic floor and soot on the wall suggested coal mining, Chernobyl and a business zone. Crash barriers provoked motor racing. FBI special agents hid beneath a grill. Fire extinguishers obviously induced fire statistics. The smart area of tiled floor inspired the grandiose arc of the worlds governments. Wood covered inspection pits became paths through the landscape. For those with an acute eye two spatial logics could be seen at play, thematic zoning overlay a more familiar pattern.

Initially we had thought we would build up with small statistics from the entrance door and place China to round them off before the rest of the hall come into view. Yet, as we pushed pieces of paper around on our diagram back in Birmingham, a new logic emerged. The proportions of the building started to suggest a map set out in Mercators classic projection with the Entrance and North America top left, Exit and New Zealand bottom right. In accordance with the map top right is the vastness of the Chinese population now echoed in the bottom left by the worlds population at three points in history. This stomach turning triptych was placed in a slightly walled-off zone perhaps suggesting its historic status. As is the way with these things, after the event it became difficult to imagine we ever contemplated any other logic.

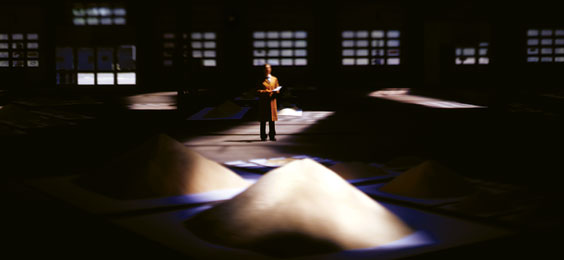

We kept the central isle clear to give the installation space to breath. We knew the hills would act visually as landmasses and if these were landmasses then the floor between must become oceans, so we floated A4 vessels on the concrete.

A major challenge came converting our fluid UK show, with its emphasis on compression and witty lateral thinking, into this huge global version. As befits a big beast, the Stuttgart show had a more measured, and powerful tread. Whole countries could now be placed side by side. Exhaustive inventories were possible, even required. Still we tried to present a mix of ideas to keep surprises and interest bubbling. We looked to mix global issues with local references. To balance large numbers representing major historic events we showed small domestic numbers. We wanted jokes along with the shocking. We became interested in scenes conjured by text describing a place, time and action represented by rice. In order to stop the Wagenhalle becoming a graveyard of official statistics, often about death, we scoured papers for less official numbers and hit the streets to record unofficial statistics.

By 18th June there were over a thousand statistics set out. The opening night was full of emotion. It was wonderful to see a large crowd sprinkled with faces familiar from our research workshops. I was too tense to be with the show in its opening hour, but later wandered in to find people engrossed, it seemed all would be all right. That night we celebrated into the night in our Green Room and emerged to find the rice glowing in moonlight, the table and globe spot-lit, seemingly miles apart. Systemnet threw its ghostly voices around the void. We caught our breath and vowed to stage a torchlight version.

So started three weeks of performance that doubled as work. Our fantastic local performers laboured in an amazingly dedicated fashion. Cleaning, translating, thinking and creating. They needed to be precise and concentrated, often in very hot conditions. Placing golden rice on crisp white paper in a dirty industrial building looked fantastic but with thousands of visitors each week maintenance duties were constant.

The show continued to develop, responding to the interests of its visitors and performers. Current affairs played their part and people started to place themselves in the landscape. The Wagenhalle leaked in heavy rain so each day was extended by covering key points in plastic at night and unveiling them in the morning. As enormous storms hit us even these covers were not enough, flooding swept away the tsunami victims amongst others, performers worked franticly to save China whilst in the real world thousands lost their homes there. With trouser legs rolled up we asked; is the metaphor growing too strong?

Slowly people talked to people and word got around. Early visitors returned recommending others. Reviews started to work their work. Finally people realised they were running out of time and could put it off no longer. The last days became a frenzy. On 10th July over a thousand people came to visit. Watching the last stragglers leave on that last day was a strange and hollow event the end somehow not just of a show, but of an era.

Performing the World Version of this show was always our big dream; that it happened barely two years after the ideas first staging seems little more than miraculous. It now looks as if the show will have a long and varied life, it even seems more world versions will be staged. Whatever happens it is difficult to image that this first version, made for Theatre Der Welt, with the people of Stuttgart, will ever be anything less than definitive.

James Yarker 7.9.5