Back-ache and 25g rice sacks. When I met James in Birmingham before flying to Stuttgart I had forgotten to factor in the need for a rigorous personal fitness regime.

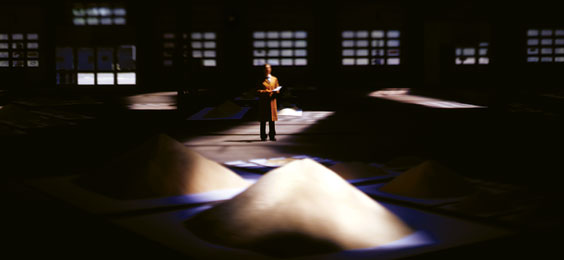

The population of the world expressed through 104 tons of Italian rice fitted into four twelve wheeler trucks. These were easily dwarfed by the location for Of All The People In All The World. The Wagenhalle, a beautiful turn of the century build, a former tram depot, arms factory and bus repair garage is vast. Karen, James and the get-in team set to with their strategy for moving rice sacks into position. Dimensions of white paper were measured, optimum angles of rice sack gradient were calculated and forklift trucks revved into action. Chalk marks were drawn on the floor and whole subject regions, continents and eras were mapped across the space. I forgot to warm up.

On Day Two of a ten day get in I felt exhausted after completing the first statistic, a grain of rice for every Brazilian Catholic. It was good to get involved directly in working with the rice instead of watching the rest of the team speaking knowledgeably about the final shape of the show. The mapping of the performance in these first three days established a really solid deadline for all of us and I felt fired up to play my part in building the show.

In the hot afternoon of Day Five I walked with James to look at the three rice mounds representing the world’s population pre-1901. Sunlight pouring through the Wagenhalle’s louvred windows cast cloud shadows across these largest of rice mountains. We stood in silence and watched the light change subtly. The show was nowhere near ready to open but there was a real satisfaction in being close to these structures. I knew how much work had gone into making them and I enjoyed their stillness.

I gradually settled into a routine based around specific tasks of measuring, weighing and cleaning. These all required physical effort and concentration. What I found tricky from the start was switching between the repetitive mechanical action of moving rice and the precision needed to make the rice fit into the narrative James was looking for.

The fresh performers arriving from the UK and our German team colleagues found my grim faced determination a bit wearing and I’m not surprised. Working on this show for five weeks made me reflect on my ability to work with others in a close team. Whilst I could listen and follow instructions it took me the first week to understand the value of balancing a need to get the show into shape with including team members in the rationale for what they were doing. It’s easy to avoid explaining your thinking when you are hauling rice all day.

The get-in and early period of performance surprised me as team members found their preferred working method and special interests very quickly. It became apparent within a few days of the opening; who preferred research to physically shaping the show. The all rounder award had to go to Sarah Archdeacon for managing to maintain a clear performance mode, research relevant statistics and shape her allotted area of the Wagenhalle without losing her mind completely.

Obvious challenges to our collective morale came with Stuttgart’s heatwave and violent storms. Soaring temperatures alternated with near disastrous flooding, which strangely seemed to reinvigorate the team and inspire them to make the show look better than it did pre-deluge. Despite the griping and shuffling which accompanies any run of a performance the team adopted a factory worker attitude to running the show. Petty hierarchies, practical jokes, surreptitious bullying and flirtation kept each shift on track with Tannoy announcements and the 6 0’clock chimes regulating our working day. Whilst I enjoyed the company of my fellow workers I found quiet time cutting paper with our guillotine. Hidden from the main floor of the show it gave me a chance to think and be mindful of a single focussed task.

Beyond the routine work of maintaining the show I met people who were pleased to tell me their stories and contribute their personal statistics to the landscape. I won’t forget the Physics professor who returned for the third time on the busiest day of the show. His story poured out in the last fifteen minutes of the final day. His personal statistic appeared in the Stuttgarter zone of the performance. Three grains of rice on A4 sheet of white paper: his mother, himself and his younger brother. All had fled from the advance of the Red Army across Germany in the winter of 1944. They had hidden in a farmhouse and been fed and sheltered by the farmer. The little brother was only a week old and needed milk to survive. The professor described cramped freezing trains, a frightened mother and a father lost on the Eastern Front. The family had survived and eventually been reunited in Stuttgart. I liked the stories which made sense of being in this city with this show.nWhen it came to leaving the on the last evening I walked the space in near darkness. The Wagenhalle hosted us for five weeks, it lent us its factory heat, dirt and elegant design, space in which to build a unique event.

Mike Kirchner, September 2005