Text from a talk given at TEDx Bonn: 17 November 2018.

Commissioned by SAVE THE WORLD

at Telekom Design Gallery

When you grow up on a small island you keep bumping into its edges and unless you leave that island it is difficult to understand how big the world is.

I was in my late twenties when, at the wheel of a powerful van, with a credit card and passport in my pocket I landed at the port of Hamburg and first sensed the vastness of the globe. From here I imagined it was unbroken road to Vladivostock, Chenni or Durban.

We were driving to Hanover because we had just made our first hit show, it was in demand across Europe so I had started to feel like a significant artist and hence a significant person. This feeling didn’t last for long. Every city we visited seemed as big and busy as the last, everyone frantically busy doing whatever they do and almost no one realised we had arrived in town to do what we do.

Back at home I reflected on my new found insignificance, I thought it may help me understand my place in the world if I understood how many people I shared the planet with. Looking up the number didn’t help. 6.2 billion, what does that mean? Even written out in full the number was ungraspable.

And this I realised was the key – the number was ungraspable. I sensed that if I could gather 6.2 billion graspable things together in a room it would then be possible to take one of them away, hold that as me and look back on everyone else. Then I would understand my place in the world.

Calculations with a set of kitchen scales suggested we would need 104 tons of rice to gather together 6.2 billion grains, enough to fill four big lorries. I was shocked and disappointed because by now I desperately wanted to build this pile.

At that time, in 2003, the UK population was 60 million and so could be represented by just one ton of rice, a manageable quantity. Whilst thinking about my big rice pile I had also been reflecting on a documentary I’d heard about babies living in prison with their mothers. This led me to think about all those people whose lives I knew so little of; how many of these babies were there in prison, how many women were in prison, how many men, how does this compare to the country’s population as a whole and, thinking about it, how many prison officers look after these prisoners and how many police officers chase criminals and how many judges pass sentence? I had a vision of that one big rice pile divided up into many smaller piles each carefully measured and resting on its own neatly labelled sheet of paper.

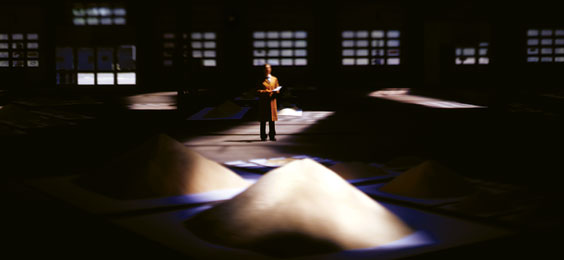

And so the performance installation Of All The People In All The World was conceived. Warwick Arts Centre agreed to host it, not in their gallery but in their foyer where everyone passing-by would see it, become curious and slowly be drawn in.

In that first performance we discovered this simple device of placing human population statistics side by side allowed us not just to make provocative comparisons and show changes over time but also to tell dramatic and tragic stories, to depict historic moments and even to tell jokes. Whilst we had expected people to find the installation intellectually rewarding, we were shocked at how emotional they became.

For some reason, possibly in part because of their humanoid proportions, visitors appeared to have a great sense of empathy with these grains of rice standing in for people. If a visitor found a rare stray grain of rice not resting on a sheet of paper they would bring it to us saying with concern “we’ve found this person, they’re lost, we don’t know where they belong”. “Don’t worry” we’d reply “we’ll take care of them, they’re in safe hands now, thank you for rescuing them”. Our audience had bought into the rice-as-people substitution more fully that I could ever have hoped.

I was excited to note that even in vast piles the granularity of the rice remains clear, every pile is demonstrably a collection of individuals, each with their own identity, who all together form a number. #6 And here we come to one of the key rules for the installation. We never show the numbers because the numbers get in the way; in standing in for the people numbers erase the people. In the same way that labels beside images on gallery walls compete with and distract from the images, so numbers would draw power from the rice, we don’t need the numbers, we have the objects to grasp.

I was surprised when people laughed at our weak jokes – twelve grains labelled EVERYONE WHO HAS WALKED ON THE MOON beside one grain, the well known moonwalker MICHAEL JACKSON.

I was more than surprised when people admitted blinking back tears – CHILDREN WHO WILL LOSE THEIR SIGHT TODAY AND DIE WITHIN A YEAR.

Charities have long known that pictures of individuals in need create an emotional response that a number cannot replicate, but this mute disempowered parade of suffering brings its own ethical concerns.

The rice is more anonymous, it is blank and this blankness invites imaginative engagement it becomes a screen for emotions to be projected onto.

Anonymity also allows the rice to be egalitarian. Everyone, no matter what their social status, their gender, race, age, health, fame or fortune is represented by a single, naked grain of rice.

In effect, as performers we are Gods in brown coats, we plunge our hands into the rice sacks and randomly select a grain. ‘Today you will be Nelson Mandela, you will be an oligarch and you, you will be living on a landfill site in Rio De Janeiro’. We are made of the same substance, we are all of equal worth and here in this room, under this same light, glowing golden, visitors will see us as such and recognise this to be true.

Within two years of its first presentation Of All The People In All The World came to Germany – we were back – this time in a tram shed in Stuttgart with a lot of rice, four lorry loads, 104 tons, we’d built a map of the world, a map measuring out human circumstance and endeavour, folly and triumph, celebration, tragedy and disgrace on a granular level, at the scale1 to 1, a map as big as the territory.

This moment had a profound impact on me. If you ever need a humbling experience try holding one grain of rice in the palm of your hand whilst surrounded by 6.2 billion other grains.

This was in 2005 and since then the installation has toured to galleries and theatres, tents, shop units, cathedrals, community halls, a gymnasium and museums. Everywhere it goes it is re-made anew with fresh statistics for that new time, in that new place, for and with new people with new histories and everywhere we go these people bring me new hope because everywhere we take the rice we find people who share a fascination with the world, their place in it and the people they share it with.

Around the world people are shocked by the same provocative comparisons THE WORLD’S DOLLAR MILLIONAIRES beside THE WORLD’S REFUGEES, shocked by the scale of us, THE POPULATION OF CHINA, THE POPULATION OF INDIA, shocked by our economics MCDONALDS CUSTOMERS TODAY WORLDWIDE, EMPLOYEES OF WALMART, EVERYONE WORKING FOR LESS THAN $2 PER DAY. Everywhere we go people display the ability to leap into the lives of others and empathise with them.

It gives me hope that a human being can show enough compassion for a grain of rice that they will pick it up from the floor and try to find it a safe home. If we can show this much concern for a grain of rice representing a person how much more concern must we be capable of displaying for an actual person?

Knowledge is crucial and empathy powerful and our show delivers both of these but even combined they are not enough. How do those of us who seek to bequeath a better world to those who follow us convert this knowledge and empathy into action, into change?#18 Ultimately it is so much easier to take responsibility for a grain of rice than the human it represents. It is safe for us to pluck a grain of rice from the floor, this costs us nothing, but to pluck someone from a leaky boat on the Mediterranean is to take on a much more open ended, costly and complicated responsibility.

It is easy to be shocked at the growth of the number of airline passengers over time, or the number of people displaced by flooding in Bangladesh, or people made homeless by other extreme weather events, or facing water rationing in Cape Town, or fighting wildfires in the United States. It is all very well to take a deep breath when you see counted out the thousand plus citizens of Chad who together each year generate only the same carbon emissions as you or me.

It is easy to be shocked and empathetic but at what point does this shock and empathy ignite and transform into action? #20 This ignition point is difficult to reach, especially if any action threatens to result in our lives becoming even slightly less luxurious than they currently are and if we don’t recognise anyone else making even these small sacrifices it is easy to think “why should I?” or “what’s the point?” Well, the point is that it’s the right thing to do and the point is to lead by example, to show it’s possible, to be one of the trend setters. The challenge is not to be a hypocrite, to say one thing and do another, to have good intentions and never follow through. Am I optimistic?

Yes, because to be less than hopeful is to accept defeat and because every day I see human empathy displayed in our granular world and watching you laugh and cry, this gives me hope.

Text: James Yarker 17/11/18

Photo Credit: Jo Hempel