Craig and I hit the port of Hamburg in a transit with passports packed and a juiced up credit card. Hanover was the plan, but now we were off our tiny island we realised there was nothing to stop us blasting trans-continental. Moscow, Delhi, Beijing, Cape Town lay at our mercy.

I’m asked where the inspiration for Of All The People In All The World came from and that exhilaration, sensing our place on the lip of a vast landmass, was certainly part of it. Two years later, we were again on tour, this time watching real cities become model cities and model cities become real cities. Each time we touched down we found another city full of people bustling about their business for whom it would be no appreciable loss if the UK and its 59 million inhabitants, including Stans Cafe, didn’t exist. This parochial small island boy was beginning to get a sense that the world was far, far bigger than he had ever imagined it to be and he was starting to wonder if he would ever be able to understand how many people he shared the planet with.

Some kindly students at Manchester Met e-mailed me back saying the task I had set was impossible. Sand doesn’t have a consistent grain size; it goes down to powder. If I was ever going to see 6.2 billion of something together to learn how many people live on Earth, it wasn’t going to be via grains of sand, or sugar, or salt and it wouldn’t be them that did the counting. Disappointed, I started hanging out at full-on builders merchants, looking at sand, pebbles and chippings. It looked great but hopeless. I trawled the Ladypool Road eyeing up the spices and prices, pepper corns, pulses and the rice. The rice, the Ladypool Road does rice big style.

Rice would be perfect I’m counting out 100 grams from my kitchen scales to get a sense of scale discrete grains of a uniform size, robust with a staple food stuff resonance. Each grain looks almost vaguely humanoid and crucially it would be far cheaper than doing the show in jelly babies. I hit the equals sign and groan, the bad news had been brewing and now it broke 100 odd tons. It was pointless costing it up. That was a hell of a lot of rice. No chance!

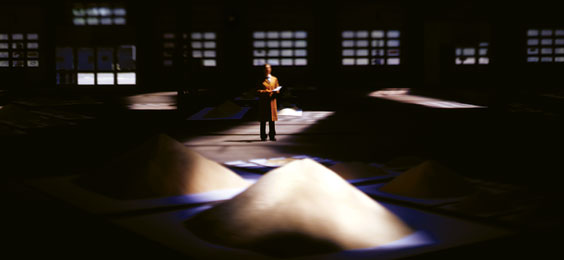

Somehow the ludicrous enormity of 100 tons of rice made the show more important to do. The world was far bigger than the far bigger I’d realised I couldn’t imagine. It had to be seen to be believed and yet, even so, 100 tons! We could divide the 100 tons into smaller amounts and see other statistics too. What would our tiny island look like in rice? 59 million grains, one ton, that would be interesting. In fact that would be interesting on its own, interesting enough to base a show on. £600 for a ton of rice, we could do that. We could do that and if it worked, who knows!

And so we did and it did and here we are, 100 tons plus on order, arriving at the Waggenhalle, Nordbahnhoff, Stuttgart, at 12 Noon on Monday, shit the bed.

As I have answered questions about inspiration I’ve mentioned the transit van and the tour of 2002. I have added my fascination with models and – “there are as many stars in the sky as there are grains of sand on the beach” – my affection for Victorian attempts to comprehend the incomprehensible. Just recently I remembered seeing Anthony Gormley’s Field For The United Kingdom downstairs at the old Ikon Gallery and realised this must have fed into my thinking unheralded. Even more recently I recalled having seen, even longer ago, an installation, Turner Prize nominated, name and artist forgotten [1], comprising rows of neon tubes covered in a layer of rice. It all goes in it all gets mixed up and, very occasionally, it comes out as an idea that, with a bit of work, turns out to be not too bad at all.

James Yarker

1.6.5

[1] Research reveals it was a piece called Neon Rice Field by Vong Phaophanit.